These days, news and social media outlets use their platforms to broadcast new and existing variants COVID 19 evolving in countries globally. Is this a new virus? How does it affect us? Many questions and many suspicions are around us! So, let us begin with-what is the variant?

These days, news and social media outlets use their platforms to broadcast new and existing variants COVID 19 evolving in countries globally. Is this a new virus? How does it affect us? Many questions and many suspicions are around us! So, let us begin with-what is the variant?

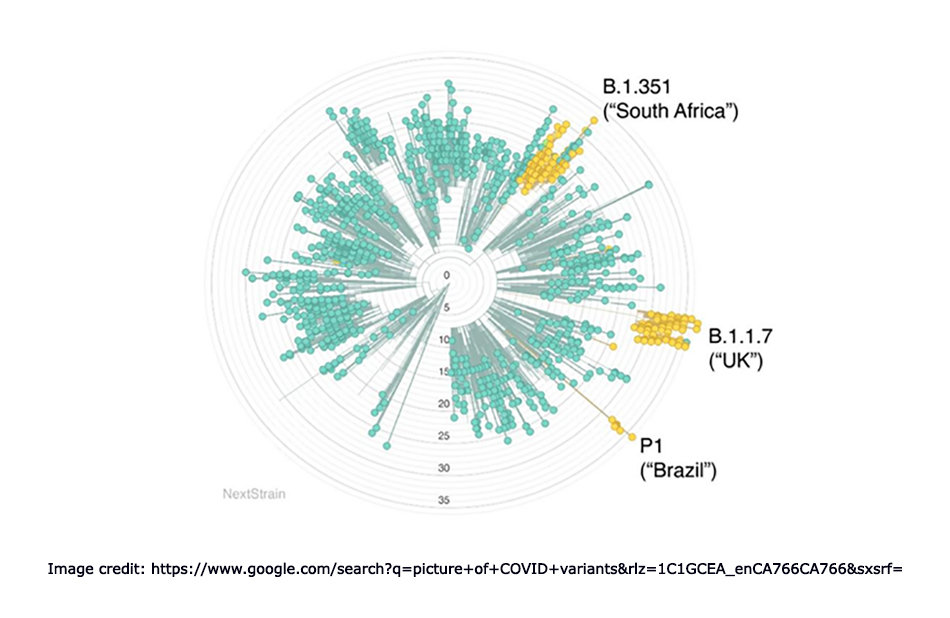

When a virus reproduces or replicates itself, it changes its characteristics somehow-which is normal attributes of the family. This change is called a mutation. Mutation in virus is neither a new nor unexpected phenomenon. All R.N.A. virus mutate over time, some more than others. A straightforward example is the requirement of up to date and renewability of flu vaccines every year, due to the course of virus induced changes. When a virus has one or more new mutations, it is called a variant of the original virus. For example, SARS COV-2 CORONA VIRUS is the primary virus, whereas B-1-1-7, B-1 351, or P-1 are variants of COVID-19. Several variants can be identified during the pandemic.

Different variants COVID-19 were diagnosed different parts of the world. B-1-1-7 was identified in the United Kingdom, B-1-351 was found in South Africa, and P-1 was detected in Brazil. Multiple variants are circulating globally. There are many classifications for SARS COV-2 variants. The common variants can be distinguished as variant of interest (V.O.I.), a variant of concern (V.O.C.), and variant of high consequences (V.O.H.C.). Facts of these three categories are as follows:

Different variants COVID-19 were diagnosed different parts of the world. B-1-1-7 was identified in the United Kingdom, B-1-351 was found in South Africa, and P-1 was detected in Brazil. Multiple variants are circulating globally. There are many classifications for SARS COV-2 variants. The common variants can be distinguished as variant of interest (V.O.I.), a variant of concern (V.O.C.), and variant of high consequences (V.O.H.C.). Facts of these three categories are as follows:

1. The variant of Interest (V.O.I.): This is a virus that has a definite genetic build that has been linked with changes to receptor binding, reduced neutralization by antibodies created against previous infection or vaccination, reduced efficacy of treatment, potential diagnosis impacted or predicted increase in transmissibility or disease complication.

This variant might require one or more appropriate public health measure including enhanced sequence of surveillance, improved laboratory depiction, or epidemiological investigations to assess its spread, severity, and risk of reinfection.

2. The variant of concern (V.O.C.): This variant has high transmissibility and more severity resulting high rate of hospitalization and deaths. This causes a substantial reduction in neutralization by antibodies generated during the previous infection or vaccination, the expected effect of treatment, and high failure of vaccination. This virus needs more appropriate public health actions such as informing WHO and local or regional level health authorities to control the spread. It necessitates extensive testing or more research to determine the effectiveness of vaccines and treatments against this variant. The health authorities may need to develop a new effective diagnostic techniques/procedure and/or modifications of vaccine or treatment plans.

3. The variant of high consequence (V.O.H.C.): This variant has a high severity of disease. Thus, there are greater numbers of hospitalization. This type has been proven to defeat medical countermeasures such as vaccines, antiviral drugs, and monoclonal antibodies.

On the way to reduce the risk and prevent the spread of the variant, we all need to follow all public health measures. For instance, reducing the number of close contacts, maintaining hand hygiene, wearing a mask, practicing physical distancing, staying at home if there are any symptoms of the disease, get tested as soon as possible if suspect of any symptoms of COVID 19, knowing the need of quarantine and isolation and of course, to be honest, to do so!

On the way to reduce the risk and prevent the spread of the variant, we all need to follow all public health measures. For instance, reducing the number of close contacts, maintaining hand hygiene, wearing a mask, practicing physical distancing, staying at home if there are any symptoms of the disease, get tested as soon as possible if suspect of any symptoms of COVID 19, knowing the need of quarantine and isolation and of course, to be honest, to do so!

To conclude, it is normal for R.N.A. viruses to change their nature through a process known as mutation. There are many classifications of variants existed in different countries. As long as there are human movements from one part of the world to another, variants can travel every corner of the world with people. Therefore, every individual has a liability in mitigating this pandemic by practicing public health measures.

For further information:

1. Volz, E., Hill, V., McCrone, J. T., Price, A., Jorgensen, D., O’Toole, Á., Southgate, J., Johnson, R., Jackson, B., Nascimento, F. F., Rey, S. M., Nicholls, S. M., Colquhoun, R. M., da Silva Filipe, A., Shepherd, J., Pascall, D. J., Shah, R., Jesudason, N., Li, K., Jarrett, R., … Connor, T. R. (2021). Evaluating the Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutation D614G on Transmissibility and Pathogenicity. Cell, 184(1), 64–75. e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.

2. Korber, B., Fischer, W. M., Gnanakaran, S., Yoon, H., Theiler, J., Abfalterer, W., Hengartner, N., Giorgi, E. E., Bhattacharya, T., Foley, B., Hastie, K. M., Parker, M. D., Partridge, D. G., Evans, C. M., Freeman, T. M., de Silva, T. I., Sheffield COVID-19 Genomics Group, McDanal, C., Perez, L. G., Tang, H., … Montefiori, D. C. (2020). Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell, 182(4), 812–827.e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043

3. Yurkovetskiy, L., Wang, X., Pascal, K. E., Tomkins-Tinch, C., Nyalile, T. P., Wang, Y., Baum, A., Diehl, W. E., Dauphin, A., Carbone, C., Veinotte, K., Egri, S. B., Schaffner, S. F., Lemieux, J. E., Munro, J. B., Rafique, A., Barve, A., Sabeti, P. C., Kyratsous, C. A., Dudkina, N. V., … Luban, J. (2020). Structural and Functional Analysis of the D614G SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Variant. Cell, 183(3), 739–751.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.032

टेक्ससको पशुपति मन्दिर निर्माणका लागि नरेश पाण्डेको १ लाख ११ हजार डलर सहयोग

टेक्ससको पशुपति मन्दिर निर्माणका लागि नरेश पाण्डेको १ लाख ११ हजार डलर सहयोग

विजय चालिसेको युगसन्धिको मूल्याङ्कन

विजय चालिसेको युगसन्धिको मूल्याङ्कन

कोलोराडोमा संस्थागत सहकार्यका अवसर एवं चुनौती विषयमा अन्तरक्रिया सम्पन्न (फोटो फिचर)

कोलोराडोमा संस्थागत सहकार्यका अवसर एवं चुनौती विषयमा अन्तरक्रिया सम्पन्न (फोटो फिचर)

ट्रम्पको आप्रवासन नीतिको असरः ६ महिनाभित्रै ३ हजारभन्दा बढी नेपाली मुलुक फर्काइँदै

ट्रम्पको आप्रवासन नीतिको असरः ६ महिनाभित्रै ३ हजारभन्दा बढी नेपाली मुलुक फर्काइँदै

सम्झनामा- डेनमार्क

सम्झनामा- डेनमार्क

हरेक बिहान हेरेर……………

हरेक बिहान हेरेर……………

क्यालिफोर्नियामा कन्सुलर शिविर सञ्चालन

क्यालिफोर्नियामा कन्सुलर शिविर सञ्चालन